According to Eric Berne, decisions about ourselves, our world and our relationships with others are crystallized during our first 5 years of life. These decisions are based on the encouraging or disparaging pattern of strokes we receive from our parents and others. Based on these decisions, we assume one of four basic psychological life positions, which to a large extent determines our pattern of thinking, feeling, and behaving.

Our early existential decisions are reinforced by messages (both verbal and nonverbal) that we continue to receive during our lifetime. It is also reinforced by the results of our games and interpretations of events.

Berne states that dysfunctional behaviour is the result of self-limiting decisions (made in childhood in the interest of survival) which culminate in an unhealthy life script.

Generally, once a person has decided on a life position there is a tendency for it to remain fixed unless there is some intervention, such as therapy, to change the underlying decisions.

The aim of transactional analysis psychotherapy is to change an unhealthy life script. This is based on the supposition that because we made the decision in the first place, we have the power to change it. Once our script is brought into our awareness, there is hope that we will be able to do things differently.

Life Positions

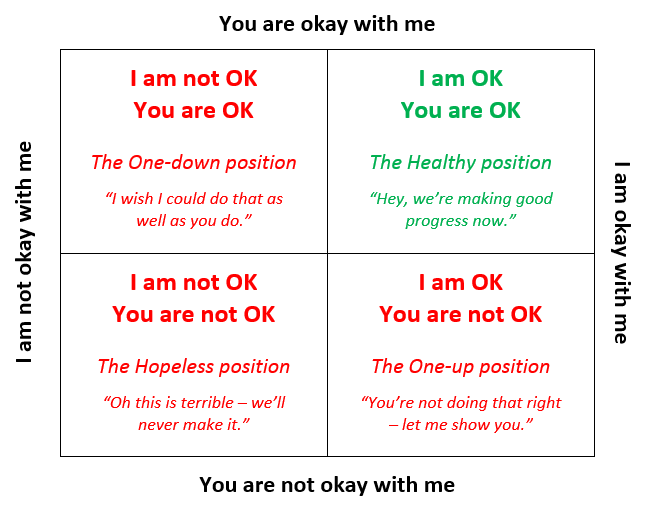

There are four life positions:

I’m OK—You’re OK

I’m OK—You’re not OK

I’m not OK—You’re OK

I’m not OK—You’re not OK

The I’m OK—You’re OK position is known as the healthy position and is generally game-free. It is the belief that people have basic value, worth, and dignity as human beings. That people are OK is a statement of their essence, not necessarily their behaviour. This position is characterized by an attitude of trust and openness, a willingness to give and take, and an acceptance of others as they are. People are close to themselves and to others. There are no losers, only winners.

The I’m OK—You’re not OK is the position of people who project their problems onto others and blame them, put them down, and criticize them. The games that reinforce this position involve a self-styled superior or one-up (the “I’m OK”) who projects anger, disgust, and scorn onto a designated inferior, or scapegoat (the “You’re not OK”). This position is that of the person who needs an underdog to maintain his or her sense of “OKness.”

The I’m not OK—You’re OK is known as the depressive or one-down position and is characterized by feeling powerless in comparison with others. Typically such people serve others’ needs instead of their own and generally feel victimized. Games supporting this position include “Kick me” and “Martyr”—games that support the power of others and deny one’s own.

The I’m not OK—You’re not OK is known as the position of hopelessness, futility and frustration. Operating from this place, people have lost interest in life and may see life as totally without promise. This self-destructive stance is characteristic of people who are unable to cope in the real world, and it may lead to extreme withdrawal, a return to infantile behaviour, or violent behaviour resulting in injury or death of themselves or others.

In reality each of us has a favorite position we operate from under stress. The challenge is to become aware of how we are attempting to make life real through our basic life position and if necessary, create a healthy alternative.

Note:

The I'm OK –You're OK life position is probably the best-known expression of the purpose of transactional analysis. That is, to establish and reinforce the position that recognizes the value and worth of every person. Transactional analysts regard people as basically "OK" and thus capable of change, growth and healthy interactions.

The four life positions were developed by Frank Ernst into the well-known OK Corral shown below:

Life Script

Related to the concept of basic psychological life positions is the life script (sometimes called childhood scripts). Put simply, the life script is the pre-conscious life plan that governs the way our life is lived out.

This script is developed early in life as a result of the messages we receive from parents and others and the early decisions we make. It can be seen as a well-defined course of action that we decide on as a child and which is maintained by subsequent events.

Script messages are seen as coming from:

- Modelling: Visible ways adults and peers behave.

- Attributions: Being told 'you're just like...'

- Suggestions: Hints and encouragement such as 'Always do your best'.

- Injunctions and counter-injunctions: Demands to not do or do things.

A potential script decision is made when a person discounts his own free child needs in order to survive. Only after several discounts does the decision become part of the script (unless the situation carried a great deal of significance such as the death of a parent or sibling). Script decisions are the best the child can manage in their circumstances and yet, yesterday’s best choice made by the child, may become very limiting to the grown adult.

Life scripts have a deep and unconscious effect on how we live our lives. They affect the decisions we make. They control what we think we could easily do and could never do. They shape our self-image. And yet we seldom realise where they come from or even do not know that they exist at all.

Life scripts are not all the same as they may also be significantly affected by individual events, such as being criticized by a teacher or bullied by other children. They also are constrained by inherited characteristics. For example, it would be unusual (but not impossible) for a short person to include being a basketball player in their life script.

There are often overall shapes to life scripts that can be expressed very simply, for example 'I am a loser' or 'I must help save the world'. Life scripts can be very detailed or they can be very vague. They can be very empowering, yet they can also be severely limiting.

People follow their script because of the pay off, a familiar feeling, attempting to avoid the loss of love and in an attempt to gain love.

An example of a life script might be the decision made by lots of boys early on in life that it’s not safe to cry and show emotions. This is reinforced by parental figures and other caregivers. As a result many men find it difficult to connect with their emotions as adults.

Another example, is that of a child, brought up in poverty, who sees celebrities on television and hears her grandmother telling her that she can be like that, and how there are people on the TV screen who started with nothing, just like her. She consequently creates fantasies and plays games of being a celebrity. Other children join in, but with her it runs much deeper. She works hard and always volunteers, even after forgetting much of her conversations with her grandmother. She ends up working in television, not as a celebrity but behind the scenes. Whilst she feels good being close to the stars, there is a strange sadness about her when she returns to her small apartment at night. She still works hard and the deep (now largely unconscious) belief that celebrity success will find her drives her on.

Script Analysis

As mentioned above, our script is developed from our early decisions based upon our life experiences. This happens at an unconscious, or at best pre-conscious, level and we may not even realise that we have set ourselves a plan.

Script analysis demonstrates the process by which people acquired their script and the strategies they employ to justify their actions based on it. The aim is to help clients open up possibilities for making changes in their early programming.

One of the techniques that therapists use to reveal scripts is to ask clients to recall their favourite stories as children. Clients are then asked who their favourite character is in the story and who they identify with. They are asked to consider the beginning, middle and end of the story. And to determine how they fit into the stories or fables and how the story is reflected in their current life.

Another way of getting to a relevant script is to ask clients to think about what they believe will happen when they are in old age. Do they believe they will be alive at 80 or 90 years old, be healthy, happy, and contented? What do they think will be on their headstone or grave? What would they like to have on it?

As a result of exploring their life script, clients learn about the injunctions (see below) they uncritically accepted as children, the decisions they made in response to these messages, and the games and rackets they now employ to keep these early decisions alive.

By being part of the process of self-discovery, clients increase the opportunities for coming to a deeper understanding of their own unfinished psychological business and, in addition, they gain the capacity to take some initial steps to break out of their self-defeating patterns.

Permissions and Injunctions

Our chosen life position is based on the encouraging or disparaging pattern of strokes we received from our parents (and others).

Parental teaching often happens at an unconscious level: when parents are excited by and approve a child’s behaviour, the messages they give are often permissions; however, when parents feel threatened by a child’s behaviour, the messages expressed are often injunctions.

Permissions are just as the word implies - giving the child permission to do something. For example, “Do think”; “Do ask for what you want”. They are the opposite of injunctions.

Injunctions are prohibitions or negative commands from a parent (often outside their awareness) and come from the parents’ Child ego state (the scared or angry Child ego state). They are expressions of disappointment, frustration, anxiety and unhappiness which come out of the parent’s own pain.

Injunctions establish the “don’ts” by which children learn to live. These messages are predominantly given nonverbally and at the psychological level between birth and seven years of age. Injunctions include:

“Don’t”

“Don’t be”

“Don’t belong”

“Don’t be a child”

“Don’t be close”

“Don’t be sane”

“Don’t feel”

“Don’t grow up”

“Don’t need”

“Don’t be separate from me”

“Don’t be the sex you are”

“Don’t succeed”

“Don’t think”

“Don’t want”

“Don’t be well”

“Don’t be you”

The child responds to these injunctions and makes a script decision. It is the negative script decisions which will possibly cause difficulty later in life.

McNeel proposed that the child makes two decisions – a despairing and a defiant one. The despairing decision is made when the child accepts the parental message - that there is something wrong with him or her. The defiant decision is made when the child tries to fight against the parental message. He/she develops coping behaviours to resist the injunctive message and master the circumstances. These coping behaviours tend to be extremes that are impossible to achieve and so are doomed to failure.

Counter-injunctions

When parents observe their sons or daughters not succeeding, or not being comfortable with who they are, they attempt to “counter” the effect of the earlier messages with counter-injunctions. These messages come from the parents’ Parent ego state and are given at the social level. They convey the “shoulds”, “oughts” and “dos” of parental expectations. Examples of counter-injunctions are:

“Be perfect”

“Try hard”

“Hurry up”

“Be strong”

“Please me”

The messages given at the psychological level are far more powerful and enduring than those given at the social level, so the problem with these counter-injunctions is that no matter how much we try to please, we feel as though we are still not doing enough or being enough.

Decisions

The following list, based on the Gouldings’ work includes common injunctions and some possible decisions that could be made in response to them:

“Don’t make mistakes.”

Children who hear and accept this message often fear taking risks that may make them look stupid. They tend to equate making mistakes with being a failure.

Possible decisions:

“I’m scared of making the wrong decision, so I simply won’t decide.”

“Because I made a dumb choice, I won’t decide on anything important again!”

“I’d better be perfect if I hope to be accepted.”

“Don’t be.”

This lethal message is often given nonverbally by the way parents hold (or don’t hold) the child. The basic message is “I wish you hadn’t been born.”

Possible decisions:

“I’ll keep trying until I get you to love me.”

“Don’t be close.”

Related to this injunction are the messages “Don’t trust” and “Don’t love.”

Possible decisions:

“I let myself love once, and it backfired. Never again!”

“Because it’s scary to get close, I’ll keep myself distant.”

“Don’t be important.”

If you are constantly discounted when you speak, you are likely to believe that you are unimportant.

Possible decisions:

“If, by chance, I ever do become important, I’ll play down my accomplishments.”

“Don’t be a child.”

This message says: “Always act adult!” “Don’t be childish.” “Keep control of yourself.”

Possible decisions:

“I’ll take care of others and won’t ask for much myself.”

“I won’t let myself have fun.”

“Don’t grow.”

This message is given by the frightened parent who discourages the child from growing up in many ways.

Possible decisions:

“I’ll stay a child, and that way I’ll get my parents to approve of me.”

“I won’t be sexual, and that way my father won’t push me away.”

“Don’t succeed.”

If children are positively reinforced for failing, they may accept the message not to seek success.

Possible decisions:

“I’ll never do anything perfect enough, so why try?”

“I’ll succeed, no matter what it takes.”

“If I don’t succeed, then I’ll not have to live up to high expectations others have of me.”

“Don’t be you.”

This involves suggesting to children that they are the wrong sex, shape, size, color, or have ideas or feelings that are unacceptable to parental figures.

Possible decisions:

“They’d love me only if I were a boy (girl), so it’s impossible to get their love.”

“I’ll pretend I’m a boy (girl).”

“Don’t be sane” and “Don’t be well.”

Some children get attention only when they are physically sick or acting crazy.

Possible decisions:

“I’ll get sick, and then I’ll be included.”

“I am crazy.”

“Don’t belong.”

This injunction may indicate that the family feels that the child does not belong anywhere.

Possible decisions:

“I’ll be a loner forever.”

“I’ll never belong anywhere.”

Redecisions

Whatever injunctions people have received, and whatever the resulting life decisions were, transactional analysis maintains that people can make substantive life changes by changing their decisions—by redeciding in the moment. A basic assumption of TA is that anything that has been learned can be relearned.

As a part of the process of TA therapy, clients are often encouraged to return to the childhood scenes in which they arrived at self-limiting decisions. Once there, the clients re-experience the scene and then relive it in fantasy in some new way that allows them to reject their old decisions and create new ones. They then design experiments so that they can practice new behavior to reinforce their redecision.

Want to Know More?

This article is one of a three-part series on Transactional Analysis.The article “Transactional Analysis – Part I” deals with Ego States and Transactions and

“Transactional Analysis – Part II” deals with Strokes and Games.